Architecture

Original Construction

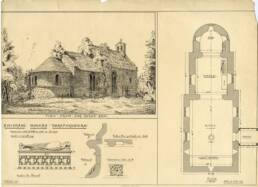

Moccas church was built in 1166 to the same ground plan and by the same masons as Kilpeck Church, but from tufa rather than sandstone. The church is a simple Norman building, made distinctive by a rounded apse which is rare in England, but frequently seen on the continent. The building also consists of a nave and chancel, with a small bell turret at the western end. It has been generally supposed that the building dates from the 12th century; however, Gethyn Jones (1979) argued for a late 11th century date, largely because of the extensive use of tufa which was declining in the 12th century.

There are two Norman doorways, north and south, and two Norman windows, north and west. The other windows are from the 14th century and in the Decorated style. The tympana above the Norman doorways are now plain, but until 50 years or so ago they were carved. Keyser (1904) said that on the north was a lion with interlaced foliage; and on the south a Tree of Life flanked by animals in the act of swallowing a human being who is head downwards , with head and one hand on the ground and the other hand against the tree. The Royal Commission on Historical Monuments described the lost tympana as showing, on the north, “much decayed carving of scrolled ornament and a beast”, and on the south, “human figures and beasts flanking a central stem from which spread crude scrolls”.

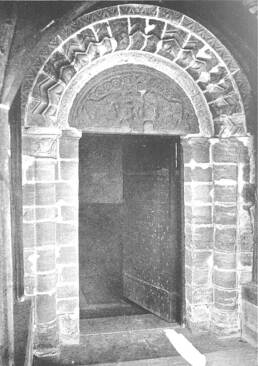

Doorways and Tympana

There are two Norman doorways, north and south. The tympana above the Norman doorways are now plain, but until 50 years or so ago they were carved.

Keyser (1904) said that on the north was a lion with interlaced foliage; and on the south a Tree of Life flanked by animals in the act of swallowing a human being who is head downwards, with head and one hand on the ground and the other hand against the tree. The Royal Commission on Historical Monuments described the lost tympana as showing, on the north, “much decayed carving of scrolled ornament and a beast”, and on the south, “human figures and beasts flanking a central stem from which spread crude scrolls”. George Cornewall wrote that the north tympanum

“was supposed to represent the Evil Spirit in the flames. Others have recognised Leviathan in the waters, or the wild boar rooting up the vine, but the first interpretation seems the true one, except the tail of the beast terminates in what appears to be a crozier.”

Looking now at the drawings reproduced in Leonard (2000) as shown below, it seems that the animal depicted on the north tympanum is a lioness, surrounded by curly foliage, while on the south tympanum, there is a tree of life which is surrounded by two lions, who seem to be in the act of swallowing the two individuals. However, it is possible that, instead of being swallowed, they are being disgorged since their heads rather than their feet are out. The Hortus Deliciarum of the Abbess Herrad of Landsberg (1125/30-1195) contains the following passage:

“At God’s bidding the bodies and limbs of people once swallowed by wild animals, birds and fish will be brought forth again, so that the intact limbs of the saints will rise again from the holy human substance.”

The lion has ambivalent connotations in both sacred and religious iconography. Medieval bestiaries underscore the animal’s many qualities, both good and bad. As it roams, the lion erases its footprints with its tail, just as Jesus did when he was sent down by the Father and kept the traces of his divine nature hidden. It used to be believed that the lioness gave birth to lifeless cubs which remained in that state until the father came on the third day to breathe life into them by blowing on their muzzles. This phenomenon was interpreted as a symbol of the Resurrection of Christ. The negative image of the lion as an emblem of the devil derives from a passage of the first letter of St Peter:

“Your adversary the devil prowls around like a roaring lion, seeking someone to devour.”

The lion is a perennial symbol of strength, and sometimes of wrath and the choleric temperament.

1850 drawings of carvings above north and south doors. With the kind permission of Longaston Press. Source – John Leonard, Churches of Herefordshire and their Treasures 2000 originally published in the Royal Commission for Ancient Monuments 1930, Vol 1, p204

The Bodleian bestiary contains two pages (27 and 29) which connect the lioness with the sin of pride, via the Book of Job. The source of the bestiary is described as follows:

“..the…text…is found in two manuscripts written between 1220 and 1250..the compiler has taken as his main exemplar a manuscript written in the late twelfth century and has added excerpts from a treatise on beasts which forms part of Rabanus Maurus’s On the Nature of Things, which includes a large number of references to Scripture.2

So maybe what we see is Pride lurking in the undergrowth, with potential consequences shown above the south door.

The tree of life is mentioned in various places in the Bible. In Genesis 2:9, it is described as being in the midst of the garden of Eden, together with the tree of knowledge, and it seems to be a symbol of eternal life. Because Adam and Eve eat the forbidden fruit of the tree of knowledge, they are expelled from the garden so that they may not ‘take of the tree of life, and eat and live for ever’ (Genesis 3:22). The result is that Adam and Eve die and descend to hell, where they have to wait for Christ’s ‘harrowing of hell’ on Easter Saturday (depicted on the font at Eardisley), where Christ rescues various individuals who could not have been saved by his sacrifice because they are already dead.

There is also reference to ‘a’ tree of life in a passage on wisdom in Proverbs 3:18. Wisdom ‘is a tree of life to them that lay hold upon her: and happy is everyone that retaineth her’ (King James version). Alternatively, wisdom ‘is a tree of life to those who lay hold of her; those who hold her fast are called blessed.’ It may be that this passage explains why the two individuals on the Moccas tympanum are holding on to the tree. Of course, at the time it was carved, the Bible was not translated into English; one cannot know how this passage was told to the carver and to the local congregation, but these carvings were probably designed as symbols for the educated and informed patrons and churchmen rather than a democratic attempt to bring education to the general population.

In Herefordshire, a tree of life is also on the tympanum of the south door at Kilpeck, the south door of the disused Norman chapel at Yatton near How Caple and on the font at Bromyard church. It is thought that the Kilpeck stonemasons were also responsible for the construction of the church and its decorative carvings at Moccas.

The overall combined message of the Moccas tympana would therefore appear to be a warning of the sins of wrath and pride above the north door and of the possibility of salvation above the south door.

Norman Arches

The interior is notable for its lovely vista of the two Norman arches opening into the chancel and apse respectively. The chancel arch is adorned with saltire crosses (another indicator of an early Norman date), the motifs being continued laterally in string courses; the arch to the apse is plainer.

Tomb

Centrally placed in the chancel is the tomb -chest of a 14th century knight, with a stone effigy. His identity is uncertain but he is believed to belong to the de Fresne family (possibly Sir John de Fresne of Sir Reginal de Fresne) who held the manor from the 13th Century. The tomb was restored as part of the 1870 restoration of the church and moved from the north wall to its present position in the centre of the chancel.

The Windows

The four major windows of the church located in the nave and chancel date from the early 14th century and are important surviving examples of the work of an English studio of the period 1130-50. The work is of high quality and distinctively from the same studio responsible for the Great East Window at Gloucester, the Tewkesbury Abbey choir windows and the Jesse tree windows at Ludlow, Tewkesbury and Bristol, as well as the local churches of Madley and Eaton Bishop. Little is known about the workshop; however, it is thought to have been based in the West Country or the West Midlands, and to have been influenced by the French style. The windows by this studio all date from 1330 to 1350.

The north and south aisle windows include figures holding the De Fresne arms. It is tempting to suggest that the glass was commissioned by Sir John De Fresne, mentioned as a patron of the church in 1306, 1320 and 1339. All of the panels contain elements of the de Fresne family who were incumbent at Moccas between 1160 and 1375. The figure elements of the windows have been lost, but without doubt the original stained glass would have filled these windows. There are the heads of niches within these surviving panels that suggest figures were sited below. Perhaps these windows were removed to let in light or stolen or smashed for iconoclastic reasons. There is an un-attributed reference in the church guide book to the a 16th century visitation where it was stated that, “church and chancel were found to be unrepaired, windows unglazed, pulpit not convenient”.

It is documented that there was some rebuilding of the windows in the nineteenth century during the restoration of the church by George Gilbert Scott Jr. about 1870 as mentioned below.

18th & 19th Century Repairs & Restoration

After the early 14th century, few significant changes were made to the church. In the late 18th century, Sir George Cornewall (formerly Amyand) undertook a series of repairs in the church and inserted a family pew with fire grate and chimney in the chancel. This was stated in 1891 by Revd Sir George Cornewall, Rector as follows:

“The Church was repaired in the beginning of the century by Mr Westmacott. At that time the south window of the apse was like an ordinary cottage window, as I can show you by a drawing. He probably added the fireplace and chimney and may have rebuilt the bell cote. The Church before it was restored by Mr George Gilbert Scott Jr., was ceiled, a semi-domical lath and plaster ceiling being in the apse and the effigy was then placed in the corner of the chancel. The chancel and apse were both raised and the windows of the chancel which had been crushed by the lowering of the walls, were restored according to their original design, there being little difficulty from the tracery which remained in determining what must be. The old glass was also restored. About half of it is new”

In the late 19th century, the Revd Sir George Cornewall decided to undertake a major restoration of the church and to install an organ. His architectural task was greatly influenced by his antiquarianism. In 1891 he lectured the Woolhope Club on the “Roman basilica plan” which was adopted by the early Christian church and reflected in the apse and chancel at Moccas. In 1863 he had visited the Roman site of Paestum where he noticed that many temples were constructed of Travertine (tufa) which had also been used at Moccas Church. Thus, Sir George required a collaborative architect rather than one hidebound by the prevailing gothic fashions. Gilbert Scott Junior was therefore an ideal choice as he had already broken away from his father’s 13th century gothic model. The Revd George raised the height of the apse and chancel using more tufa from the estate, and when that ran out, from near the river Teme .The heightening of the apse and chancel necessitated the rebuild of the Romanesque chancel arch and the provision of a new roof. A new floor was laid using the existing floor slabs. The windows needed new tracery and mullions and were reglazed but with the original stained glass reinserted.

The Romanesque windows in the apse were repaired and given “hard arches”. Both doors were restored, and a new porch was added for the south side, based upon the 14th century timber porch at Thruxton. The internal plaster work was removed from the walls which were repaired and re-pointed. New ceiling boards were put up in the 15th century manner with 54 carved wooden bosses designed by Scott. A stone altar was placed in the apse, and wooden stalls were placed in the chancel, four placing the altar for the congregation and six facing across the chancel for the celebrants. The correspondence between Sir Gilbert Scott Junior and Sir George Cornewall makes no mention of altar rails, and today’s rails are Jacobean; brought to Moccas from Willersley church in the 1970’s. The oak pews, pulpit and reading desk were produced by Franklin and Sons and are late gothic in detail. At the west end of the church, Scott inserted a massive tie beam with arched braces, producing a frame for the decorative work behind. A vestry was created, and stairs inserted to the bell chamber. This was hidden behind a fine oak screen, boarded in the vernacular manner with narrow overlapping slats, crenellated in the 15th century style.

The organ was built by R W Walker and Sons and placed in the organ loft above the vestry. Whitehead (2019) writes:

“Here we encounter the olive green and orangey-red that dominates the ensemble. Kempe and Co’s printed arabesque papers are separated by vertical strips, painted blue and gold as heraldic poles. The top of the panelled balcony is finished with a briar rose frieze, derivative from Morris and Co. Above the console, flanked by red panels, a canopy curves forward, embellished with laudatory exclamations, with the gothic letters painted on scrolls. The composition is crowned with the pipe case which breaks forward in the baroque fashion and is enriched with late gothic fretwork, set in margins of more blue and gold piping. On the bottom of the pipe case a royal blue frieze, enriched with golden sunbursts, separates the loft from the pipes. Finally, on either side is the great expanse of olive-green panelling, with the margins picked out in black and central squares of pierced quatrefoils, seen against a black and white ground with a gold patera at the centre. The panelling is terminated with a green and red briar rose frieze, leaving a stretch of stonework visible either side, under a green ceiling, suggesting that some mural decoration was planned but not executed. It remains a wonderful composition, unparalleled anywhere else in Herefordshire”.

Contemporaries recognised that George Gilbert Scott Junior was an exceptional architect; ‘scholarly and sound in style’ but also ‘individual and interesting’; an architect of ‘remarkable and exceptional ability’ whose work showed ‘delicate refinement without weakness’. Sir John Betjeman thought that Scott Junior was ‘the greatest architect of the Victorian era’. Whitehead (2019) writes that

“Sir George, it seems, chose well and let Scott get on with the work and took credit for the glory of it thereafter”.

Pevsner, 1963, “The Buildings of England” writes:

“ St Michael’s, Moccas, if it were not for the bellcote and some tall Decorated windows, which help to let light into the interior, would be the perfect example of a Norman village church.”

Simon Jenkins, 1999, “ England’s Thousand Best Churches” gives Moccas Church two stars and the following entry:

“There is no village, just an Adam mansion set in a deer park sweeping down to the banks of the Wye. Remember those who have trodden this place before” bids the vicar in his guide. Today we tiptoe gently across what is a private estate, past a genteel wall of clipped box. Moccas takes its name from the Welsh for a pig and a moor, Mochyn and rhos.

The small, neat church consists of nave, chancel and apse in a descending sequence. The inside is Norman at its most theatrical. The view from the west end is of retreating arches with zigzag mouldings. The stone is tufa limestone, almost pumice. In the centre of the chancel lies the star of the show, an effigy of a medieval knight. His legs are crossed and there is a dog at his feet, the first wrongly supposed to indicate a crusader, the second that he died in his bed, He lies with light shining on him from the chancel windows. Winter evenings must be eerie events, as if the congregation was summoned to await the knight’s resurrection and admonition , like Don Giovanni’s Commendatore.

George Gilbert Scott Junior’s jolly organ case fills the west end of the church, recognising the role that colour once played in medieval architecture”.

Text kindly provided by Doctor Rachel Jenkins

Source Material

Jenkins S., 1999. England’s Thousand Best Churches. Allen Lane. Penguin Press.

Gethyn-Jones E 1979. The Dymock School of Sculpture. Phillimore. Chichester.

Keyser C.E., 1904. A List of Norman Tympana and Lintels. Elliot Stock. London.

Leonard J., 2000. Churches of Herefordshire and their Treasures. Herefordshire: Logaston Press

Pevsner N., 1963. The Buildings of England: Herefordshire. Penguin

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Richard Perkins for his detailed help in deciphering the Moccas tympana.