History

Summary

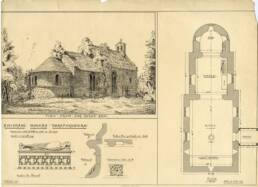

Moccas Church is a rare example of a two cell early 12th century Romanesque church and shares a sub Roman/Celtic background with a number of other churches in south west Herefordshire. It was built to the same ground plan and by the same masons as Kilpeck’s church, but it is constructed from tufa rather than sandstone. Its predecessor was originally dedicated to St Dubricius who founded a monastery at Moccas, while the present 12th century building is dedicated to St Michael and All Angels.

The early history of the church intrigued the Revd Sir George Cornewall (1833-1908), the rector and owner of Moccas Court and its associated estate, who restored the church in 1870-71. He employed George Gilbert Scott Junior (1829-97), a fastidious Anglo-Catholic architect who worked within an Arts and Crafts milieu and collaborated closely with his knowledgeable patron. St Michael’s has an outstanding interior: an early Christian chancel and apse and, from the hand of Charles Eamer Kempe (1837-1907), a ravishing organ case for the large Walker organ (built in 1871) which, together with the case and Bailey’s hydraulic engine, was restored in 2020.

Early history of the church

There is charter evidence of an early church at Moccas between the 6th and 9th centuries AD, possibly ruled by an abbot at Madley or Bellimore. Around 620 AD, Moccas had an abbot named Comeregius. These monastic sites may have been built on an island on the Wye extending from Eaton Bishop to Moccas. Archaeological investigation has not yet revealed the exact site of this earlier church.

It was claimed in early Welsh sources that the regional saint Dubricius or Dyfrig was born in Madley, in about 450 AD, son of King Pepiau of Archenfield, and became a teacher and leader to other saints. He founded a religious school at Hentland, near Ross, and then moved to Moccas. One legend says that St Dubricius left Hentland at the bidding of an angel who told him to found a monastery at a place where he would find a white sow with her piglets. He found the place further up the River Wye “well wooded and abounding in fish” which he called Moccas or “the moor of the pigs”. The discovery of a sow with her pigs is a favourite theme in the Lives of the British Saints. The use of the pig appears to be linked with the belief that a white sow and her farrow would mark a divinely chosen spot and is perhaps based on the legend of the founding of Rome. The reason for the move from Hentland to Moccas is not known but may be because of the need for improved communications, as Moccas was close to both the Chester to Caerleon road and to the main route into the west of Wales. Although Dyfrig founded a number of other monasteries, he is said to have lived chiefly at Moccas, preaching and teaching the clergy and people. There are four accounts of the life of Dyfrig, of which the main one is found in the Book of Llandaff, compiled in about 1150.

There is also an account of Dyfrig in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of Britain, which was published in 1147;a ‘Life’ written by Benedict of Gloucester; and a condensed version by John of Tynemouth. The Book of Llandaff contains charters or grants of land made to Dyfrig and his followers. The Life states that his teaching shone through Britain “like a candle upon a stand” so that the whole British nation preserved the true faith without any strain of false doctrine. Geoffrey of Monmouth records that Dyfrig was also primate of Britain and legate to the papal see and “was so remarkably pious that by merely praying he could cure anyone who was ill”. It is also stated that Dyfrig resigned the archbishopric and became a hermit, his long-held ambition. Unfortunately, Geoffrey cannot be relied upon, and the references to the archbishopric and metropolitan see are anachronistic as such positions and institutions came about much later and were unknown in Britain in Dyfrig’s time. Another legend says that Dyfrig owned land in Caerleon and that he crowned King Arthur there. These legendary links with the Roman town indicate his close connection with Romano-British Christianity. Certainly, Dyfrig’s stature within the early British Church is undisputed, and records of some of his foundations do exist in the Llandaff Charters.

It is said that pestilence laid waste to Moccas about 600 AD and that the last known abbot of Moccas was Bishop Comeregius. Moccas Abbey then slipped into obscurity and was recorded in later charters simply as a church. This earlier Celtic church was dedicated to St Dubricius. The church’s dedication to Dubricius was probably replaced when Anglo-Norman culture held sway, and when the rebuilding of the present church in Norman times gave the opportunity to rededicate the church from a little known Welsh saint to a more internationally recognised one, St Michael. In Roman times, a god named Moccus occurs in Gaul who is equated with Mercury. Mercury was also regarded as the guardian of flocks and herds, with the hunt and chase in wooded areas. St Michael was active in the heavens and so became a Christian substitute for the pagan god Mercury. The name “moccus” means pig in Welsh, and the Herefordshire Mochros in the 12th century Book of Llandaff refers to Mochros as “moor for swine”.

Early history of the locality, village and estate

Moccas has probably been inhabited since Neolithic times at the latest, with a number of significant Neolithic findings documented in the surrounding hills, including the spectacular barrow, Arthurs Stone, and the more recently discovered Neolithic Halls of Dorstone Hill. More information on this can be found in the Archaeology section.

Roman Britain begins with the conquest by Emperor Claudius in AD 42. For a few decades in the middle of the first century AD, the Marches formed the western boundary of the Roman Empire. It is difficult to know just how deeply Romanised the Welsh Borderland became. However, there was a Roman town of Magnis at Kenchester on the Wye, some ten miles away from Moccas. One legacy that may have survived the end of Roman Britain in the Marches was Christianity. Church dedications provide valuable hints about the degree of British survival in the face of pressures and influences from outside Britain. During the 7th century, the Anglo Saxons established political control over the Welsh Borderland, but this control was often unstable, and west of the Wye, many place names and field names remain Welsh in origin, including Moccas.

In the early Middle Ages, many churches belonging to Celtic saints were rededicated to fashionable Norman saints. However, there was often considerable opposition to this process and the proposed Norman saints were frequently rejected locally. A compromise was often made by rededicating the church to the Virgin or to St Michael and All Angels, as seems to be what happened at Moccas.

The Normans came as conquering feudal lords to a region that in 1066 had very few towns and a scattered rural population. Before their arrival in the late Saxon period, the Borderland had been politically unsettled: local border skirmishes were common, and on a larger scale the region was coveted by both the Anglo-Saxons and the Welsh. There was no fixed western Anglo-Saxon boundary, only a border which was shifting with the ebb and flow of conquest. Until the early 1060’s the Welsh held the initiative, with the English on the defensive, so Edward the Confessor had already introduced a number of Norman lords into positions of power in the borderlands in the 1050’s. The Normans found the Welsh borderland very attractive with geographic and political similarities to Normandy and Brittany. Whereas the conquest of England was achieved within 20 years, the conquest of Wales took over 100 years after the Battle of Hastings. The Marches formed the base from which this conquest was achieved, and the Normans’ ambitions and feuding have left a deep impression on the landscape. King William devised a scheme by which the Marches were administered as semi-autonomous earldoms based on the Saxon towns of Chester, Shrewsbury and Hereford. Within this framework, the land was divided between Marcher lords: in all, some 153 separate lordships which technically did not revert to their mother counties until the act of Union 1536. Within each lordship one or more castles were built, and these castles formed the nuclei on which the border boroughs were subsequently created. The parts of Wales conquered by the Normans came to be known collectively as the Welsh Marches to distinguish them from the unconquered parts, which were known collectively as Wales or Wales proper. The Normanised Marches of Wales was very different from Normanised England. The lords of the Welsh Marches were allowed to exercise extensive judicial powers in return for bringing the Marches and Wales under Norman control. These lords had jurisdiction over all civil and criminal cases, high and low, with the exception of crimes of high treason. They established their own courts and had unique rights of unlicensed castle building and of declaring and waging what was called private war, whereas a lord of an English estate had none of these privileges and held his lordship as a direct grant from the King. The first Norman castles in the Welsh Marches were made of earth and timber (motte and bailey), and many were later rebuilt as stone. Herefordshire’s first stone built castle is probably at Snodhill, just over the hill from Moccas. Moccas castle, now no longer visible, was a motte and bailey castle.

Moccas is itemised for tax purposes and military services in the Domesday book (suggesting it had been under English control for some time). The Moccas estate was placed in the Stretford Hundred, and divided between the minster church of St Guthlac’s in Hereford ( Moccas: 2 hides which pay tax. 6 villagers and 3 small holders with 4 ploughs. 1 Frenchman. Value 30s) and William the Conquerer’s physician, Nigel the Doctor (Moccas: Ansfrid holds from him. Ernwin held from St Guthlacs. 1 hide. In lordship 1 plough). Nigel or one of his tenants built an earthwork castle overlooking the Meres, which is a remnant of the large earlier glacial lake that had separated the monastic site from Woodbury Hill and Moccas Hill.

By the middle of the 12th century, both parts of Moccas were in the hands of Walter de Fresne. In 1293, his descendant Hugh de Fresne began building a castle at Moccas, but was arrested by the sheriff, having failed to comply with feudal law and seek a licence from the king to crenellate. The new works may have been on the site of the Home Farm and intended to replace the earthwork motte and bailey castle overlooking the Meres. The stone castle was said to be ruinous by 1375. The de Fresne family held the estate until it was acquired by the Vaughan family in the reign of Henry VII (1485 -1509). Throughout the Middle Ages, the incumbent at St Michael’s is described as a rector, confirming that the living was never impropriated by another religious institution and subsequently downgraded to a vicarage.

It is notable that Moccas is a dispersed village, with its two clusters of houses more than half a mile from the church, which is close to Moccas Court and Home Farm. The oldest houses in the village are 16th century, and so it is possible that the village was once much closer to the church and the presumed earlier monastic site, and that the village moved further away from the church at some previous stage, possibly in response to successive waves of the plague in the 14th century.

We have no evidence that the church suffered particular damage during the Reformation, although this might suggest why the lower panels of the 14th century windows were removed. In 1587, in a return to the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Bishop of Hereford, Herbert Westphaling, named the rector of Moccas as Lodovicus Prosser, classified as an ordinary Presbyterian preacher. The Patron of the parish is named as Watkin Vaughan, with Henricus Vaughan written in the margin.

In 1642, a Puritan’s Survey was compiled for Sir Robert Harley, MP for the County. Here, ‘Mockas’ is described as “a vicaridge worth 601i per annum. Mr Taylor is the Rector, non-resident being also the vicar of Bps.Upton where he liveth”, and Mr Henry Vaughan is Patron. It is something of a relief to know that Mr Hart, Curate, is termed “a constant preacher”, whereas at various other parishes including neighbouring Dorstone, over the other side of the hill, the Rector is said to be “neither constant preacher nor of good life”!

Later history of the church and estate

By the end of the 17th century the Moccas estate was in the hands of the Cornewall family. Sir George Amyand (1748-1819) married Catherine Cornewall and assumed the surname Cornewall in 1771. Between 1835 and 1868, the Moccas estate was owned by Sir Velters Cornewall. He died without heirs, so his younger brother, Revd George Cornewall (1833-1908), already Rector since 1858, then inherited the estate, undertaking the dual role of managing the estate as well as the church.

The Revd George Cornewall had long been interested in ancient Celtic Christianity and was well aware of Moccas Church’s architectural significance. His interest influenced the choice of architect for the 1870 restoration of the church, and the installation of the organ and case (for more information on this click on the Architecture section at the bottom of this page). Sir George selected George Gilbert Scott Junior, a partner of George Frederick Bodley who in the 1860’s was consulted widely in Herefordshire.

Text kindly provided by Doctor Rachel Jenkins.

Source Material

Kinross J., 2015. Castles of the Marches. Stroud: Amberley Publishing.

Morgan F.C. 1959. A puritan’s Survey of the ministry in the County of Hereford made and sent to Sir Robert Harley, Member of Parliament for the County, about the year 1642 AD. Transcribed from the manuscript no 206 belonging to Corpus Christi College, Oxford. (Transcript available from Rachel Jenkins).

F and C Thorn. (Eds.) Domesday Book: Herefordshire. Compiled under the direction of King William. London: Phillimore Press.

Rowley , T 1986. The Welsh Border-Archaeology, History and Landscape. Stroud: Tempus Publishing.

Shoesmith R 1996. Castles and Moats of Herefordshire. Herefordshire: Logaston Press

Herbati Westphaling, 1587, Survey of the Diocese of Hereford (Transcript available from Rachel Jenkins)

David Whitehead 2019. The church of St Michael at Moccas, Herefordshire Transactions of the Woolhope Naturalists Field Club, 67, 92-107

Zaluckyj S, Zaluckyji J 2006. The Celtic Christian Sites of the central and southern Marches. Herefordshire: Logaston Press.